Closed Captioning for Family Guy Is Brought to You in Part by

When Is a Caption Close Enough?

YouTube'southward notoriously nonsensical auto-captions are improving. But there's a deeper problem.

In March, Rikki Poynter flew to Orlando for a YouTuber convention. The result, Playlist Live, boasted a roster of performers who had collectively racked upwards billions of views: a sixteen-year-old who put elastic bands around a pumpkin until information technology exploded, the twins who played the evil stepsisters on Jane the Virgin, a guy who pranked people from within a snowman suit. Poynter, whose own YouTube channel has more than 85,000 subscribers, was invited to speak equally part of a panel on mental wellness. But she also arrived with a bulletin for her fellow internet celebrities: Your video captions are terrible.

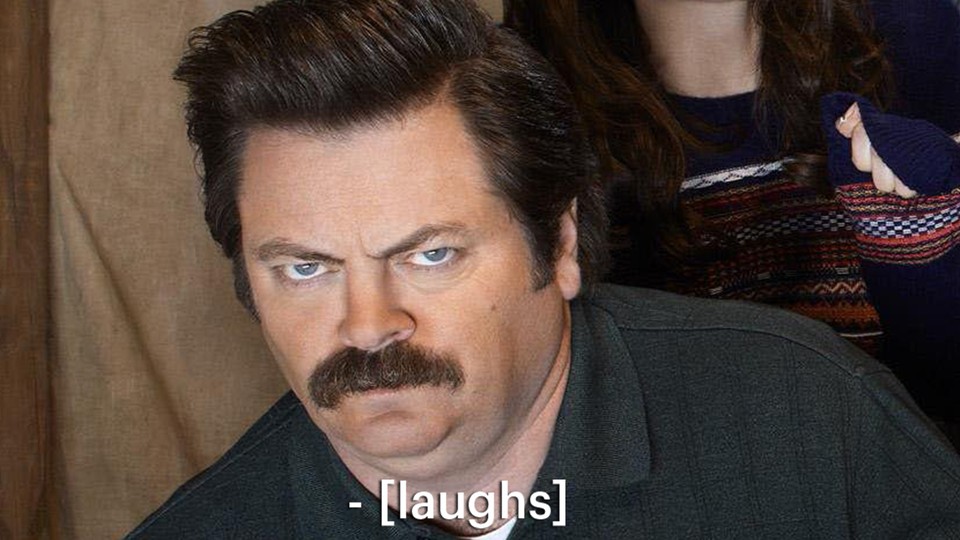

Since 2015, Poynter, a deaf 28-year-onetime, has built her following around a campaign she calls #NoMoreCRAPtions. In her videos, she asks YouTubers to ditch the automatic captions that YouTube itself generates, which are notorious for delivering run-on sentences studded with nonsensical or occasionally obscene phrases. Take Jimmy Kimmel Live's Guillermo Rodriguez knocking back a shot of maple syrup and cheering "Quondam Anna!" (He'south really saying "O Canada!") Or the influencer Emma Chamberlain declaring that once her aeroplane lands, "I'll be embarrassed." (She'south proverb "I'll be in Paris.") 1 video from Playlist Live rendered "Check out their berth" as "Check out their boobies."

In hundreds of videos, tweets, letters, and handwritten letters, Poynter has urged creators to write their own captions or employ professionals to aid go the job done right. She's inappreciably a techno-skeptic: Similar many people who place as deaf or Deaf (deafened describes a medical condition; Deaf denotes a cultural identity), she has embraced social media to connect with others in her customs. But #NoMoreCRAPtions highlights how impressive advances in assistive technologies such as automated captioning tin can obscure these technologies' imperfections. The campaign is Poynter's way of pushing back confronting any misguided notion that deaf people alive in a technological hereafter that hasn't yet arrived for everyone else.

For television broadcasts, the Federal Communications Committee oversees captioning, a legal requirement under the Americans With Disabilities Act; the aforementioned legislation requires movie theaters to make airtight captioning bachelor for most films. YouTube, however, doesn't fall under FCC jurisdiction, and has so far eluded regulation under the ADA. While film and idiot box employ fleets of human stenocaptioners and voice writers to ensure that captions run into the required standards, YouTube'south automatic captions (visible when viewers click a push at the bottom of a video) are created past speech communication-recognition software. Trained on a vast database of language gleaned from the web, the software uses probability to guide its choice of words and phrases: If the ii previous words were daily do, the next word is more probable to be routine than orphan.

Poynter insists that proper captions should not just fit the right words to a video's audio content—a feat that automation struggles to attain—but as well use correct grammar and punctuation, describe sounds like the eerie creak of a door or the crackle of gunfire, and differentiate betwixt speakers so deafened audiences know who's talking. Although the term craptions predates Poynter'southward entrada, her efforts have struck a chord, drawing international media attention and setting off waves of advocacy by hearing YouTube stars. After watching i of her videos in 2015, the LGBTQ-rights activist Tyler Oakley posted a video for his half-dozen meg subscribers explaining how to add together captions and why they matter. Recently, deaf fans rejoiced when, in a Facebook annotate, the British radio personality Phil Lester announced his commitment to ameliorate captioning.

"Until Rikki had reached out, captioning my videos had not crossed my mind, every bit I know that YouTube auto-captions all videos," Emma Lock, besides known as Emzotic, a British former zookeeper whose channel features tips on caring for behemothic snails and bearded dragons, told me over e-mail.

Fifty-fifty with the moving ridge of adept will, though, it'southward hard to tell who has truly committed to Poynter's message. She says that many creators caption for a while earlier quietly letting information technology slide. (A representative for Oakley told me that since 2017, all his videos take been manually captioned by a paid transcription service. Lester did not respond to a request for comment.) YouTubers sometimes balk at the time and money it takes to create their own captions or to hire others to do and so. Some creators brand a healthy living from their videos, but most struggle to churn out content and concenter sponsors, frequently while working other jobs.

In a few of her videos, Poynter offers viewers a promo code to get 10 minutes of professional person captioning for free from a company called Rev (the service Oakley uses). I of a number of players in the cheap-captions market, Rev charges consumers a dollar per minute of sound and promises an accuracy charge per unit of 99 percent. Bulletin boards where transcriptionists and captioners assemble tend to paint a grim picture of life equally a Rev freelancer, withal. "A monkey at the zoo gets paid better than y'all," someone wrote on the anonymous employer-review site Indeed.com. (Rev's CEO and co-founder, Jason Chicola, says that transcriptionists are generally paid 50 cents per minute of finished sound, and defended the pay rate as acceptable for someone who tin can caption quickly and accurately.)

YouTubers who can't or won't pay for a service like Rev can turn to crowdsourcing. YouTube'south community-contributions feature allows all viewers to submit their own captions for a video, with the permission of the video's creator. But when the characteristic outset launched, some popular channels quickly filled upwards with emoticons, LOLsouthward, and faux captions that commented on the action on-screen. Some channels became known for their dissonant captions, similar the comedy channel Markiplier. YouTube responded by instituting a vetting process. Before publication, proposed captions can at present be flagged by other contributors, which triggers a review by YouTube's human moderators (automatic systems also appraise the reliability of contributors in order to filter out pranksters). Past default, information technology's the oversupply that performs quality command: When enough votes of approval have piled up, captions go live regardless of whether the creator has reviewed them.

To satisfy the demands of #NoMoreCRAPtions, YouTube could, in theory, require that all video creators must add their own captions or rent someone to do and then. Liat Kaver, a product manager at Google, which owns YouTube, pointed out that such a dominion wouldn't necessarily ensure that video creators would do a expert job. It also might exclude some creators, such every bit "people who are illiterate, but upload videos to YouTube," and "denizen journalism or creators that are registering events as they happen (e.g. Arab Leap)," Kaver, who is herself deafened and uses a cochlear implant, told me over email.

A second option would be for YouTube itself to hire people to explanation videos. When I asked whether Google would consider doing so to voluntarily run across ADA requirements, a spokesperson responded that the company had nothing further to add.

The other—and perhaps almost probable—possibility is that engineering science will simply grab up. Car-captions, Poynter notes, are really getting amend, pushed forward in part by a growing demand for captioning from businesses with international workforces for whom English language is a 2d language. Rev, the captioning visitor, now offers its own automatic oral communication-recognition software on its sis site, Temi, for a lower price than its human-captioner services. The company notwithstanding extols the superiority of human transcriptionists, only claims that computer-generated transcripts are becoming competitive with those made past people.

This rapid comeback of auto-captions gets at the tensions #NoMoreCRAPtions brings to low-cal. While assistive technologies do end up working wonders for some deafened people, these technologies tin can overpromise effectiveness and convenience. Hearing aids, for instance, can neglect to capture certain frequencies. Cochlear implants, for those who choose to utilize them, usually crave years of auditory-exact grooming. (Some people come across the cochlear implant as tantamount to cultural and linguistic genocide.) The ADA mandates that people with disabilities should have equal access to public goods and services, but regarding captions, information technology'southward difficult to say exactly what that means. How accurate is accurate plenty? Rev's human captioners are held to a standard of 99 per centum accuracy, while its automated captions achieve an accuracy rate of virtually 85 to 90 percent. Google declined to provide a number, only told me that YouTube'southward voice communication-recognition accuracy improved past 50 per centum from 2015 to 2017.

The FCC has no real metrics for measuring accuracy. A spokesperson told me that the agency has been stymied by a lack of public consensus on how to set quantitative standards. The National Association of the Deaf, meanwhile, "believes that applied science will progress to the point where automated captioning will meet acceptable levels of accuracy, but also believes that it will be many years before such an acceptable accuracy rate is achieved," the association'south CEO, Howard A. Rosenblum, told me over email. The association is currently suing Harvard and MIT over lack of captioning on their e-learning videos posted on YouTube. While the platform itself is not subject to ADA regulations, the association contends that content posted there by sure businesses and organizations is.

Equally YouTube's auto-captions move into the realm of good enough—coherent, only still flawed—hearing individuals and institutions might marvel at assistive technology to the point that they consider the problem of access to online videos solved. Just practiced enough, of course, isn't the same as equal. Poynter runs upwardly against this conflict often, even in the existent world. In advance of her panel at Playlist Live, she asked the festival to provide a professional transcriber to explanation the talk in real fourth dimension to assistance her follow along. The 24-hour interval she arrived in Orlando, the captioner canceled. Poynter says that Playlist made a meaning effort to find another transcriber, but no ane was available. (The festival did not respond to requests for annotate.)

Poynter ultimately had to rely on American Sign Language interpreters, even though she's more comfortable post-obit a conversation with transcriptions. "It sucks, but … what tin yous do?" Poynter tells her audience in a video dispatch from the border of the bed in her hotel room. "Information technology's something. Hopefully it'll get improve."

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2019/08/youtube-captions/595831/

0 Response to "Closed Captioning for Family Guy Is Brought to You in Part by"

Post a Comment